Aleppo, Syria December 17, 2016 (2018)

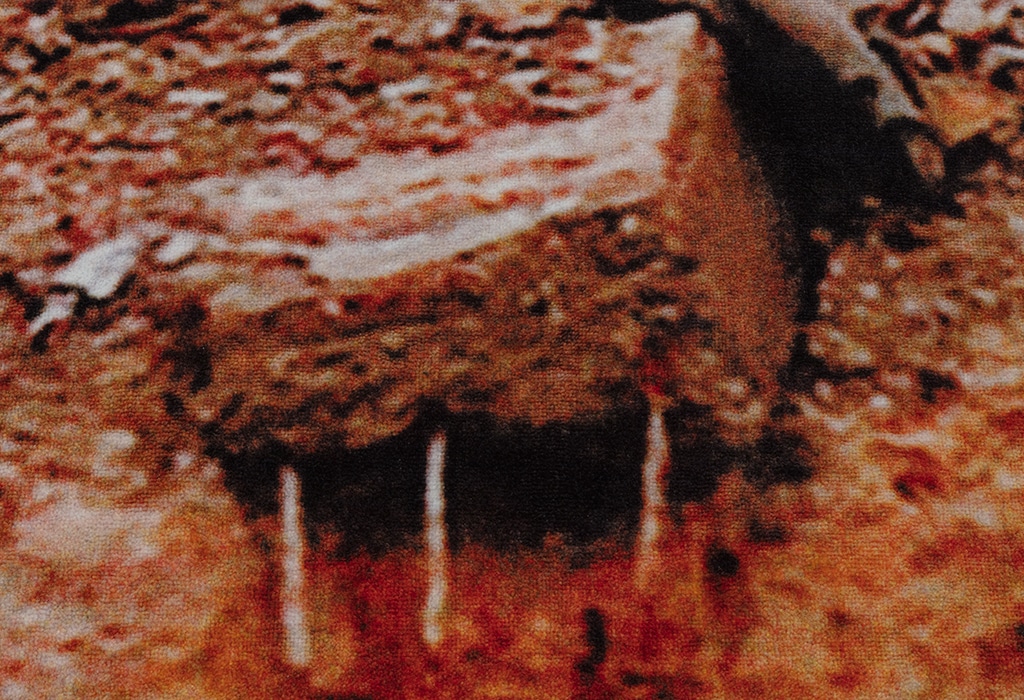

Custom printed nylon tufted carpet, specialized lighting

Aleppo, Syria December 17, 2016 is a site-specific installation that questions the political efficacy of photography from conflict zones, but more specifically the steady stream of images from the Syrian Civil War. While these photographs document the harsh realities of the war, they are also sometimes criticized for feeding what critic Michael Kimmelman refers to as “normalized indifference.” Such photos are perceived as urgently needed catalysts, but their familiarity can breed disinterest.

What kind of engagement does photography ask of us as viewers? As Ariella Azoulay notes in her book The Civil Contract of Photography (2008), “When and where the subject of the photograph is a person who has suffered some form of injury, viewing of the photograph that reconstructs the photographic situation and allows a reading of the injury inflicted on others becomes a civic skill, not an exercise in aesthetic appreciation.”

In 2010, Gisele Amantea visited Aleppo shortly before the uprising that led to civil war. While the present installation is born of this experience, it is also part of the artist’s long-term engagement with the politics of the decorative and the ways it reinforces social structures and relations rooted in inequality.

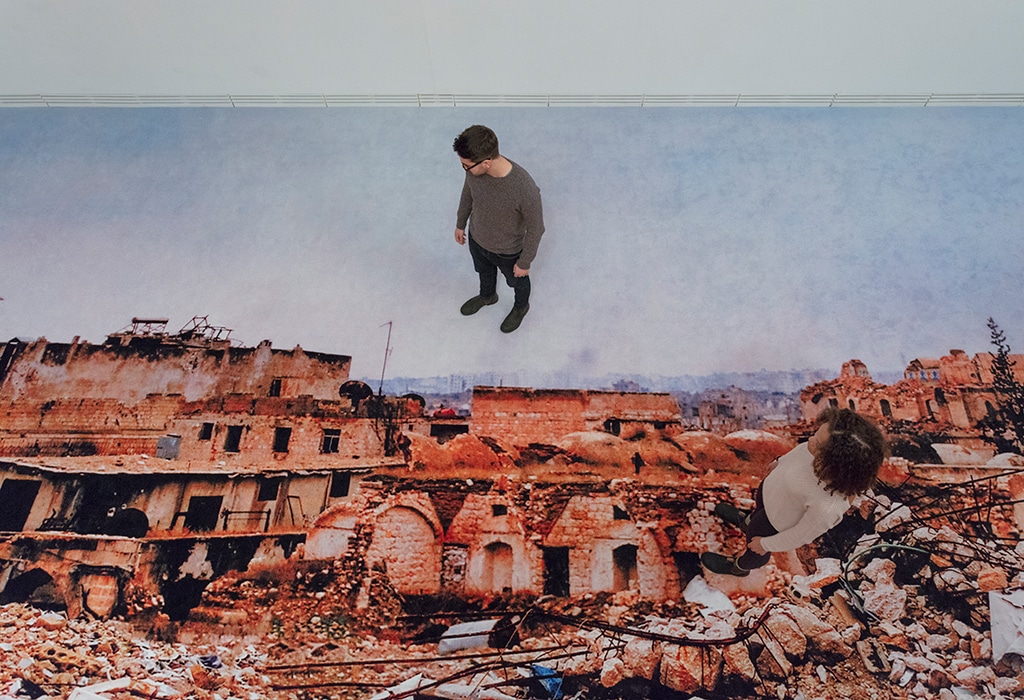

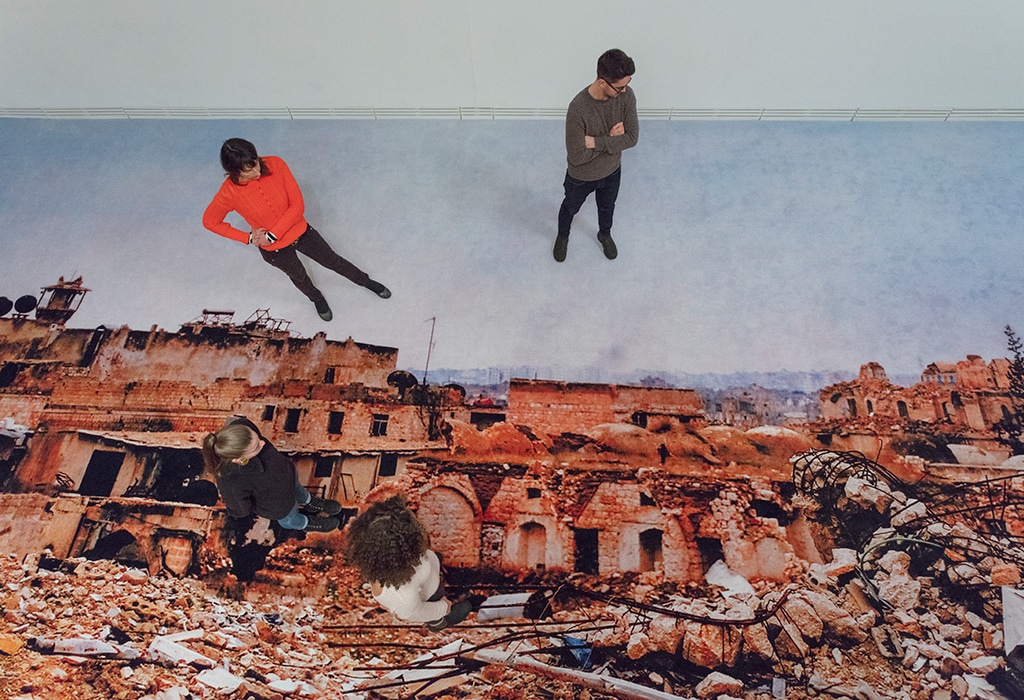

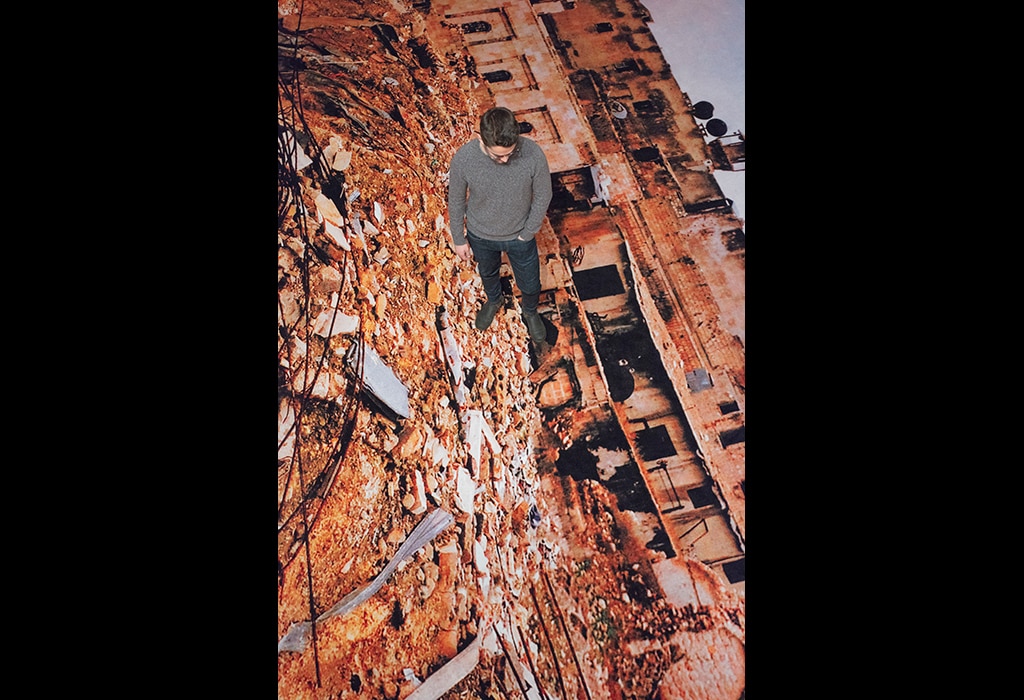

Visitors to the gallery encounter a carpet printed with a documentary photograph of the ruins of the Carlton Citadel Hotel, a luxury hotel that once stood opposite the Citadel of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site destroyed in the ongoing conflict. Although this building was originally constructed in 1890 as a state hospital, it also served as a nursing school before being renovated into a hotel in 2010. At the time of its destruction in 2014, it was being used as a barracks for the Syrian army.

Originally taken for Reuters by Omar Sanadiki, a Syrian photographer living in Damascus, the image is devoid of human life. Up close, it presents a blurry and indistinct topography. When viewed from the balcony above, however, it resolves into a disturbing vista. At this enlarged scale, we literally enter the picture, which is transformed into an architectural space, a ruined landscape, and a theatre set against whose backdrop we are positioned as “actors.”

Historically, Syria has been a famous producer of fine carpets—cherished luxury items that are often treated as assets to be sold in hard times. Before the Civil War, Aleppo was an important market for such carpets, which were sold in the souks of the Citadel not far from the hotel. While Amantea’s choice of materials clearly references this tradition, as a product of Western industrial manufacture her carpet also raises associations with less precious floor coverings, such as doormats. This ambiguity is in keeping with the artist’s oeuvre, which often raises difficult questions without imposing moral judgements.

Text by Emily Falvey, curator of the exhibition Here Be Dragons, Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario, September 17 to December 9, 2018.

Dimensions: 7.1 x 14.63 m (23′ 3″ x 48′)